Biden administration ensures that Trump 2.0 has the toolkit to strengthen strategic ties with India.

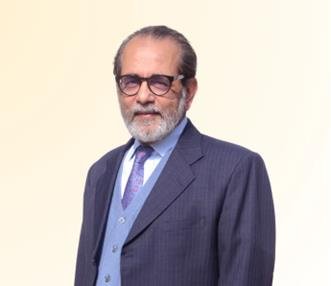

Interview with Rakesh Sood, former Indian diplomat and Special Envoy of the Prime Minister for Disarmament and Non-Proliferation, on U.S. National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan’s visit to New Delhi.

In his final visit to India as the U.S. National Security Advisor, Jake Sullivan provided a long-awaited assurance to give a push to bilateral nuclear cooperation—the delisting of key Indian nuclear entities. Sources indicate that these could include the Indira Gandhi Centre for Atomic Research (IGCAR), the Bhabha Atomic Research Centre (BARC), and the Indian Rare Earths Limited (IREL). While this move signals progress, challenges remain—ranging from legal frameworks to geopolitical considerations—that will shape the future of the strategic technology partnership.

In this interview, we explore Ambassador Rakesh Sood’s insights on these latest developments and the broader implications of the India-U.S. Initiative on Critical and Emerging Technology (iCET) in strengthening India-U.S. ties.

Hely Desai: What do you make of the outgoing National Security Advisor (NSA) Jake Sullivan’s visit to New Delhi and his announcement on lifting restrictions, just two weeks before President Trump’s inauguration? Additionally, with the External Affairs Minister (EAM) S. Jaishankar meeting both the outgoing and incoming U.S. NSAs and Secretaries of State ahead of the curbs being lifted, what significance do you attach to the timing and context of these diplomatic engagements?