The exchange of gifts between countries has a long history. Two famous examples are the hollow wooden horse that the Greeks gifted to the city of Troy, and the French gift of the Statue of Liberty to the U.S. Given recent media coverage of Qatar’s reported $400 million gift of a Boeing aircraft to the U.S., this gesture is likely to remain part of public memory for some time. The gift has sparked conversation both domestically and internationally about diplomacy and the propriety of accepting such gestures.

In May 2025, the issue of aircraft gifting also brought a moment of levity in a tense conversation between President Donald Trump and South African President Cyril Ramaphosa. The South African President joked that his country did not have a plane to gift, to which President Trump responded that if there were one, he would accept it. Qatar’s gift also attracted the attention of American legislators. Earlier in the month, the Democratic Senate leader introduced a bill to prohibit any foreign aircraft from being used to transport the President of the United States.

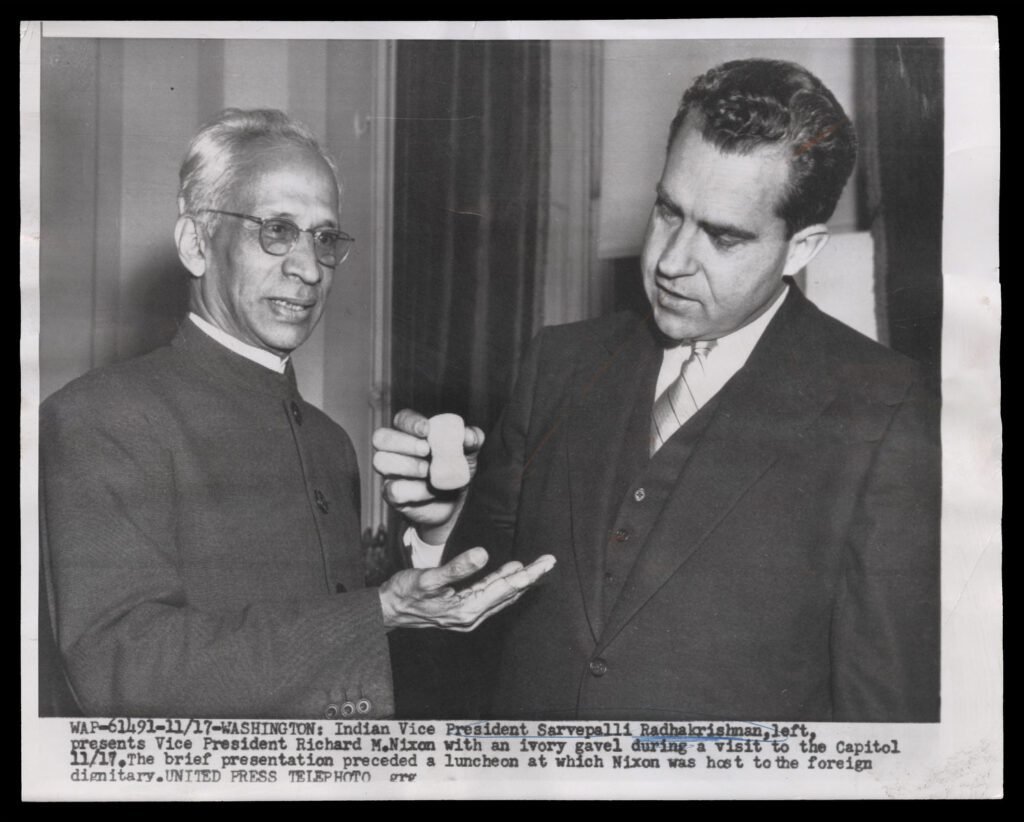

The exchange of gifts between countries through their heads of state has traditionally been symbolic and devoid of controversy. Such exchanges are part of softer diplomacy. When India became independent, Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru engaged in what came to be known as “elephant diplomacy,” gifting elephants to the children of countries around the world. For example, between 1953 and 1954, Nehru and Chinese Premier Chou En-lai exchanged several gifts. It began with Nehru gifting an elephant named Asha (Hope) to the children of China.

Premier Chou responded by sending a pair of spotted deer, a pair of red-crested cranes, and 100 goldfish of 20 different varieties on Nehru’s birthday. The Chinese embassy even chartered an Indian Airlines Corporation plane to transport these gifts and their three attendants to India. The plane flew from Calcutta to Rangoon, then to Hanoi and Hong Kong, to bring the animals back. As a token of appreciation, Indian authorities initially decided to send mango saplings of different varieties to be planted in the People’s Park in Canton (now Guangzhou).

However, since it was not the planting season, the Chinese Premier was instead gifted tea, coffee, and cashew nuts. Toward the end of December 1954, Chou En-lai replied to Nehru, acknowledging the gifts. He wrote, “I have the firm conviction that the deep friendship between our two peoples and their common desire to work for peace have provided the prospect of broad development for the friendly cooperation between China and India.” Along with the letter, Premier Chou also sent 200 tins of mild Chinese cigarettes of the type that Nehru preferred.